In 1985 I saw the film Diva (1981) directed by Jean-Jacques Beineix and managed to get the music. I was struck by the story in which the diva is unwilling to have her voice recorded until she heard it played to her by an admirer – a post office clerk involved in underground deals and car and scooter chaces and fights, and so on. I liked the whole scenario of a underworld involved in the potency of an opera singer and her purist notions of her own voice.

I put the music on and began to choreograph to strictly complement the music, not changing the order of the tracks, and without allowing the film to leave my attention. In the film the story and the music were deconstructive in nature, otherworldly and gorgeous, dark and illuminated. Her opera gown/costume was stolen from her dressing room by the clerk. The opera house teemed with peeling paint. I loved the detail. I affirmed that I did not have to rearrange music from the cassette tape. I took it as ordered from beginning to end. Nothing was to be altered from the diva’s perspective in every respect. I could relate to her sense of privacy and the mystery of being discovered even though she had an unquestioned public persona. Her semi-reclusive nature in the film appealed to me. But there had to be precision to extract the essence of this story as it pertains to a mystery about myself.

I was also attracted to the film because the diva was black, played by Cynthia Hawkins, the first time I witnessed a black soprano, and the mystery of her liberation did not easily leave me - as a South African.

See more about the film in Wikipedia: Diva (1981 Film)

Around the same time I encountered a philosopher whom I thought would have shared my ideas of absence and presence as metaphor for South African existence. I received a 15-page article from Johan Degenaar called Writing and Re-writing. His entry to the paper was a quote by Derrida:Nothing is anywhere ever simply present or absent. It was my first access to deconstructive theory.

I immediately began to explore my dances as repositories for my newly found vocabulary: dance can be deconstructed; the body and her being in space could be altered into an almost hologrammatical entity. I could be much larger than what I really was on stage, balletic movements could rapidly become ‘dark’; an arabesque, perfectly executed with profile to audience, was actually a horse. My two hands appeared to be doing the same movement to ambient music, but one was busy accelerating the other, still showing signs of the original movement but gradually transforming itself to become an entity on its own veering in an out of familiarity, tricking the eye into thinking that two hands belonged to the same person.

The quote The presence of absence, the absence of presence began to make sense to me in the psychotic existence of South African identity, being White, having political power, but being afraid, living in a world of interracial/interrelational taboo with a group of people who infiltrated my life around every corner. The fear of White existence, the fear of presence as White in certain living areas that were Black, the fear of having power and the indignity of making use of it, the schizoid existence of privilege, absence in presence and vice versa, finally began to find an artistic outlet in highly controlled choreography to the voice of the Diva.

Degenaar introduced language above perception as the necessary condition of understanding: it would overcome three myths. The myth of the given, the myth of the innocent eye, and the myth of the immediacy of understanding. But speaking would also be replaced by writing—a move from immediacy to mediacy. Inherently writing also created distance and a possible new way of understanding.

My dances to these strict pieces of music, strict lighting arrangements and spatial arrangements embodied a new understanding by virtue of distance, a sobering of embattled biography still not visibly relieved of its political impact on my life as young woman and artist who had not had an intellectual entry into art-making as such - purely working from instinct but now from the idea of ideas.

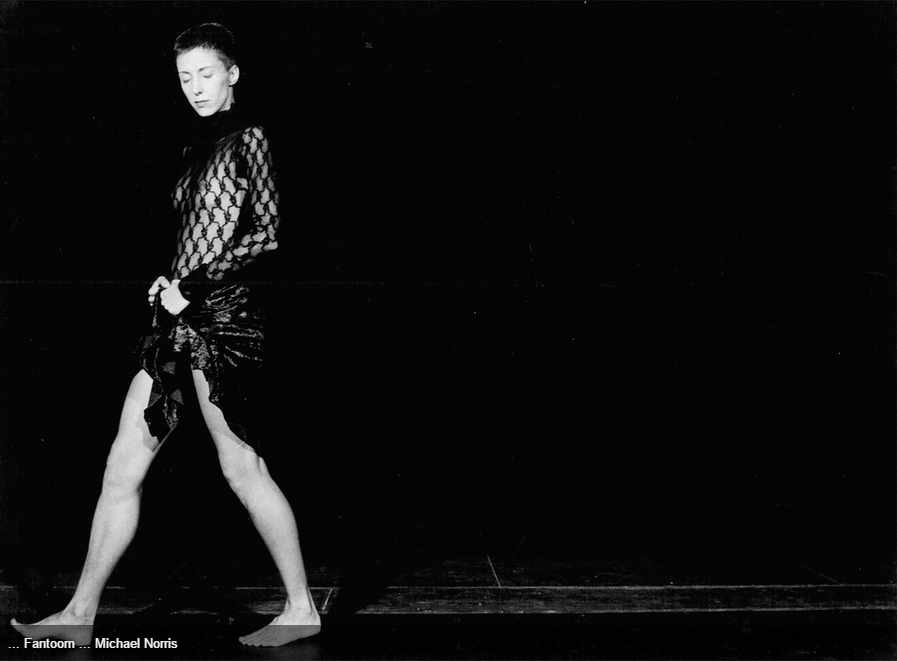

By this time none of this influx of ideas was taken into the realm of gender construction in my work. Difference was not yet a felt intellectual entity which I could engage with. I designed my costume of black velvet and black stretched net, and a black veil. The visibility of my torso through the net, the elongated poloneck over my head without a head at the end, or the upside down postures to get a body to look like a person without a head, upside down dress, overturning the body’s hierarchy, with my legs as arms, was sorcery to the eye. I felt I was contributing to another writing, an arche-writing, to use Degenaar’s term, with the body.

For the first time the words ‘White man’ landed for me in a paper where his condition in the world was considered an entity outside that of shame, guilt. He was being looked at as subject within language that attempted to understand what had been happening to him. And I stood in the shadow of that debate hoping to hear something about myself. Still afraid. Waiting. Hoping to be released from the burden of political power. Dancing.

Since ballet, for me, was analogous with the hierarchy of Western dance, its training became increasingly problematic in the manner in which it impacted on the dancer’s body over years. It was stylistically “pure”, pristine as cultural form and strongly situated as the portal to any dancer’s ability and acclaim in the Western sense of the word. However, through deconstruction I then had a theory with which I could make an arabesque a horse. My body could become both with equal ease. My fingers knocked against my breastbone nervously with intermittent urgency. And I could stand in fifth position with arms in an equally perfect fifth position---with no regard for the spectators’ sightline. It was a matter of rearranging signs that had already been danced, introducing new relationships. It was my aim not to provide the onlooker with anything for which understanding was final. Degenaar’s words to the same effect applied to writing; mine was dance. He used the pen, I used my body. Alternatively, he used thought, I used my life as portrayed through my body.

The revelation in this article - that my work might have the possibility of being read differently by all omnipresent and powerful critics, and that the aesthetic evaluations of art and the historical context of dance-art would have deeper significance than the blatant “balletic” comparisons that critics had at the time to evaluate any dance by - offered relief and belief in my own work at the time. Degenaar quoted Culler as : “Texts can be read in many ways; each text contains within itself the possibility of an infinite set of structures, and to privilege some by setting up a system of rules to generate them is a blatantly prescriptive and ideological move.” (Culler J Structuralist Poetics. London: Routledge and Keghgan Paul. 1975:242)

I had great difficulty to let my work speak for itself, knowing that as in the South African social dimensions of apartheid, my work was subjected to a ruling culture and it was not defining the whole of culture, and could certainly not define the whole of me if it had only a limited matrix of genres in its possession. As it was the task of South Africans to re-read culture, I offered a strategy that was tempting to be read as classical, but empirically collapsible should one have wished to be willing to see meaning behind movement. Here I was intimately linked to the society that produced me and consumed what I offer, rather than being seen as a barefoot ballet dancer or just ‘different.’ There was mediacy possible behind the immediacy of theatrical interpretation. I was hoping for an appreciation mediated by intertextual traces, as Degenaar says. (p12). By analogy with Degenaar’s statement that “all writing is a continuous re-writing” which entailed an ongoing situating of signs differently, all dance was a continuous un-dancing of technique, a scribble on the edge that disturbed the text sufficiently to not reach closure and “cultivat[ing] the illusion of the self-contained art-object”. (p13)

The Black diva was exposed to her talent and art via the cunning whereabouts and maneuvers of the ‘other’ in the film. Her gown was swooped through a city on a motorbike, her voice was played on a Nagra recorder in a lonely opera hall (where danger was lurking in the dark), and over and over in what appeared to be a shadowed mechanic’s garage. But the revelation to herself of her artistic genius was only possible in this manner rather than on the insistence of her eager and greedy agent to whom she would never succumb to record her voice, anyway. It highlighted symbolic acts in terms of domination or of liberation. And I felt I had an introduction, intellectually and aesthetically to being human in this tragedy called South Africa.

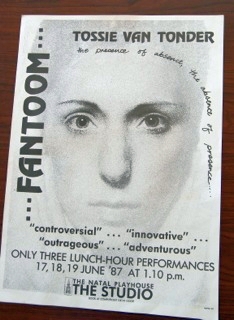

The title …FANTOOM…: if it was not enough that I referred to the existence of a phantom limb as a form of perception of what is un/known to me, I felt it did not say enough about this condition. So I decided it had to be written in Afrikaans, especially for its alliteration with my surname. Then I put the dots before and after to signify the ephemeral, the infinity, the unplace-able, the un-nameable, the dancer who won’t….

MUSIC: DIVA by VLADIMIR COSMA